© Fotolia/Marco2811

Setting New Rules – The Free Trade Agreements of the European Union

The central pillar of rules-based and open trade should always be the WTO. It is the first and best way to open markets worldwide and to set new rules for trade. However, free trade agreements (FTAs) can be – and have been for years – a sensible complement to the multilateral trading order. With the WTO in crisis, these agreements further increase in economic and political pertinence, central to the EU’s foreign trade policy.

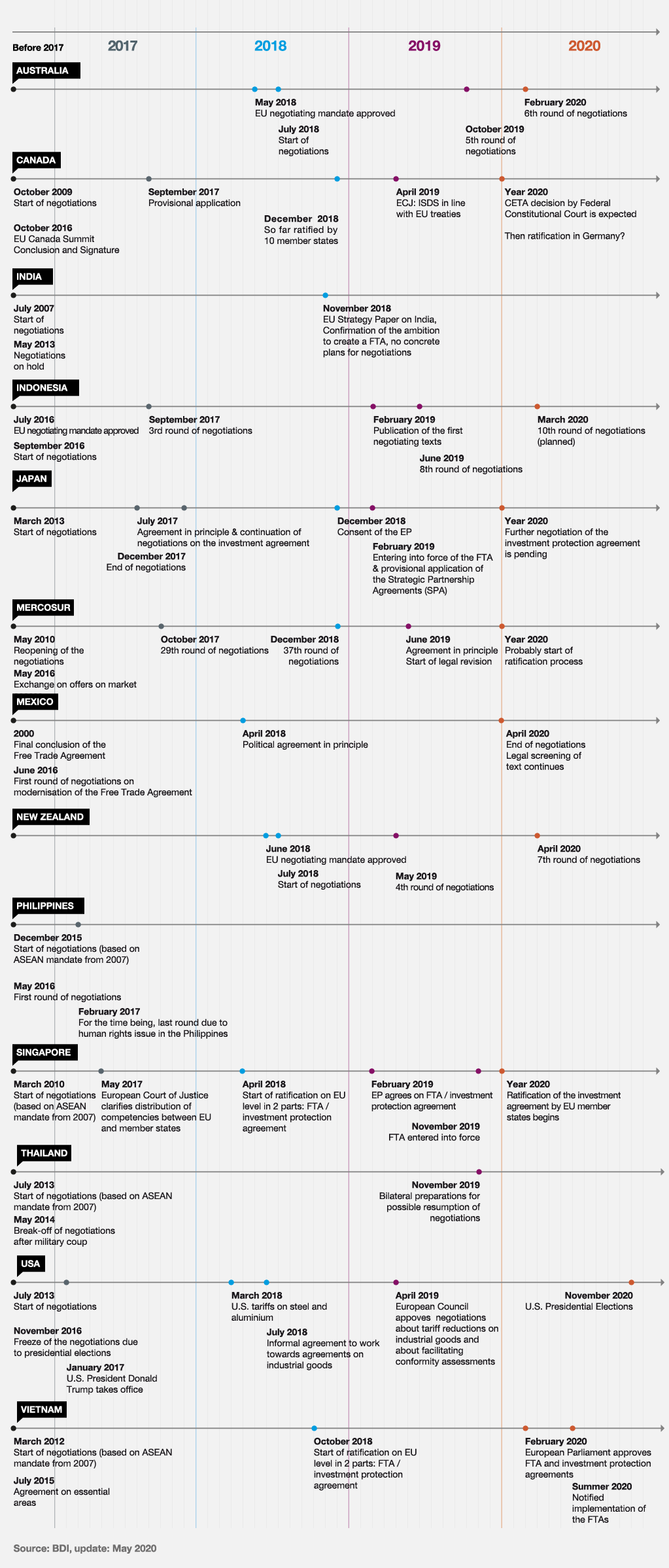

The EU has concluded FTAs with 37 partners that have come fully into force, including for example with South Korea, Japan, and Singapore, as well as FTAs with 43 partners, for example with Canada and Ukraine, that are provisionally applied. In May, the EU and Mexico also reached an agreement in the negotiations for modernising the existing agreement. Negotiations for new FTAs are ongoing with 19 countries, including Australia and New Zealand.

Negotiating FTAs is anything but easy. Due to the complexity of modern FTAs, negotiations can take years. In late June 2019 – some 20 years after the start of negotiations – the European Commission reached an agreement in principal on the FTA with the Mercosur countries. Months of work must be invested into the details before the agreement is ready to be signed. Legislators do not expect the presentation of the agreement until the second half of 2020.

The EU’s modern FTAs intend to do more than simply dismantle tariffs. In addition, they are to improve market access by removing non-tariff trade barriers (for example, through regulatory cooperation), liberalising trade in services, and opening markets for public procurement. These agreements go well beyond the scope of the WTO. They include competition rules, access for foreign direct investment, and regulations to ensure sustainability (labour and environmental protection). The EU seeks to modernise older agreements with Chile and Mexico, which contain only basic economic aspects.

European Responsibilities and Ratification Process

Negotiations of FTAs, however, have become increasingly controversial in the wider public. A case in point were the negotiations for the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), the FTA between the EU and the United States. The negotiations for the FTA between the EU and Canada (CETA) were likewise contentious. Months of tug-of-war by political actors seriously challenged the efficiency and reliability of European decision-making in trade policy, damaging the EU’s international credibility and effectiveness.

The European Court of Justice (ECJ) decision on the FTA with Singapore in May 2017 clarified which areas of an FTA fall under the exclusive competency of the EU and which components require the ratification on the Member State level. This important decision allows for more clarity in future FTA negotiations. Prior to the ruling, all FTAs were always ratified by both the Union and the respective national parliaments of the member states. Since the ruling, the approval within the Member States is only necessary when parts of the agreement fall within shared competence. In Germany, for example, the Bundestag and if applicable, the Federal Assembly would vote in their entirety on the agreement. In May 2019, the ECJ also found that the newly designed Investment Court System included in CETA is compatible with European law. This question had been the subject of months-long ambiguity.

Many of the EU’s trade agreements are still in the ratification process and only implemented on a provisional basis. CETA is a mixed agreement. The chapters which fall into the exclusive competence of the Union are currently applied on a provisional basis with ratification still ongoing in the member states. The chapter on investment protection, on the other hand, is not yet applied, pending ratification by the members. The EU and Singapore have negotiated an FTA and an Investment Protection Agreement, two separate treaties. The trade agreement entered into force in late 2019 after the European Parliament and the Council gave their consent. The Investment Protection Agreement is yet to be ratified by all Member States according to their own national procedures. In mid-2019, the EU signed a trade agreement and an Investment Protection Agreement with Vietnam. The FTA with Vietnam was approved by the European Parliament in February 2020; Vietnam previously complied with EU demands to observe international labour standards. The FTA is expected to enter into force in summer 2020.

Policy Follows Judicial Decisions

Following ECJ guidelines, the EU now designs FTAs to ensure that they remain under exclusive EU competency. Thus, areas such as investor-state dispute settlement and portfolio investment have to be negotiated in separate agreements. This clear division of areas into different agreements allows FTAs to be ratified and enforced swiftly and reliably by European legislators. Such a separation is, however, not possible where trade agreements are an integral part of political association agreements (e.g. with Ukraine, Mexico, Mercosur, etc.). These treaties remain mixed, if only because of the foreign and security policy components (the EU negotiations with Mercosur are based on a 20-year-old mandate and do not include investor-state dispute settlement).

Of course, this clear division does not mean that the ratification of FTAs lacks democratic legitimacy. The competence for trade policy rests with the EU; since the Lisbon Treaty, trade agreements must be ratified by the European Parliament. Nevertheless, Member State parliaments should be informed in a timely and comprehensive matter about FTA negotiations in order to provide for a well-informed public debate. A transparent negotiation process includes moreover the publication of the negotiation mandates of the European Commission.